The real story of Amazon’s success: Profiting off of small businesses

NEIL TRACEY: How does Amazon make its money? This question might seem like it would be simple to answer, but it is widely misunderstood. For years, business journalists and analysts have held that Amazon Web Services (AWS) is the real profit driver behind the tech conglomerate. This line of reasoning holds that Amazon web services are both the fastest growing and most profitable part of the business while Amazon Marketplace’s profitability is limited by low margins. Typifying this, Business Insider ran the headline in 2017 “Here's where Amazon’s profits are coming from (Hint: it's not from online shopping).” However, contrary to this narrative, Amazon’s most profitable business is Amazon Marketplace. Why is the mainstream belief wrong? Amazon has constructed this misconception through financial accounting techniques which mask not just online shopping’s profitability, but also the damage Amazon does to third party sellers.

Amazon closely guards the profitability of its Marketplace. In fact, unknown to many, Amazon does not report profitability for Marketplace. Amazon only reports profitably for Marketplace combined with Prime and its own retail division. This sly reporting technique disguises the true profitability of Marketplace because Amazon loses money on Prime — so the losses in Prime reduce the reported profitability of Marketplace. This accounting strategy is a blatant attempt to hide the profitability of Marketplace. Amazon was shown once again hiding the profitability of its Marketplace during the 2019 House Big Tech hearings, lawmakers asked Jeff Bezos for information on just how profitable Amazon Marketplace is and Amazon refused to provide the data.

So how profitable is Amazon’s Marketplace? A recent report by Stacy Mitchell at the Institute for Local Self Reliance estimated the profitability of Amazon Marketplace by piecing together research on online advertising margins, the limited data disclosed by Amazon, and existing estimates on online marketplaces margins (including by Brian Nowak, and Michael Pachter). The report found that Amazon raked in 121 billion dollars in revenue and 24 billion in profit in 2021 from Marketplace and only 13.5 billion in profit from AWS.

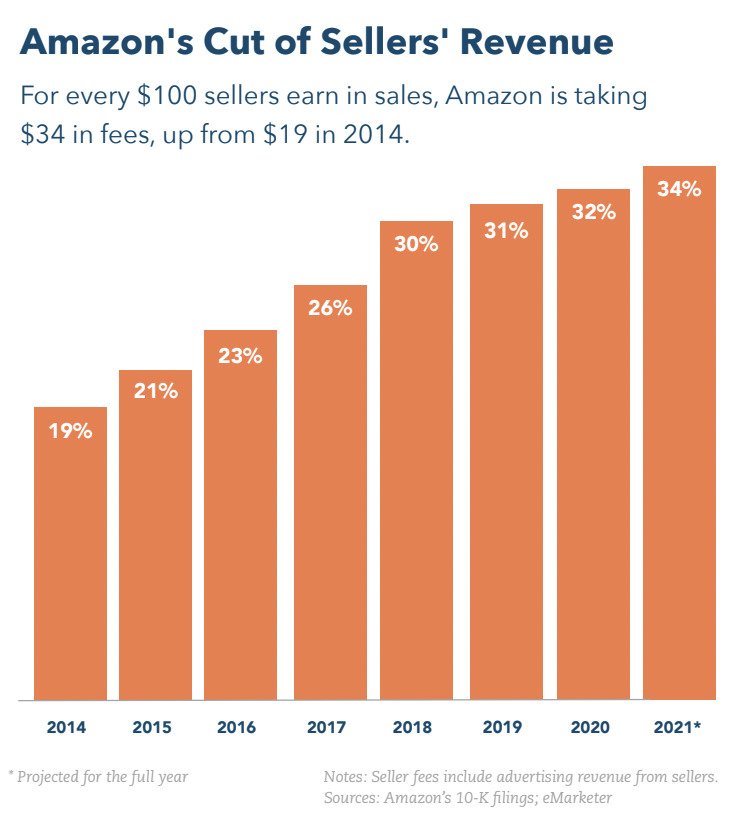

Amazon hides this profitability because its profitability comes from Amazon using its market power to charge exorbitant fees for third-party sellers on Marketplace. In 2014, Amazon charged 19% of sellers’ revenue, today, that figure has jumped to 34%. These fees come from three main sources: referral fees, advertising and fulfillment fees.

Referral fees are simply a cut of every sale that Amazon takes out of every sale in exchange for the use of Marketplace. The other two, advertising and fulfillment fees, Amazon presents as optional but are, in fact, far from it. In recent years, Amazon has expanded the amount of paid slots that pop-up on any given search on Marketplace— these paid spots require an advertisement fee. This reduces the number of well-positioned (first or second search page) that are given out to non-promoted products. Whereas sellers might have been able to get a good spot in the search results simply based on reviews a decade ago, today, they are forced to pay advertising fees in order to be profitable on Marketplace.

Similarly, Amazon presents its fulfillment fees as optional when, in practice, they are not. Amazon bases its placement of products in Marketplace in part based on whether or not the sellers use their fulfillment services; Fulfillment By Amazon (FBA) handles, packages, and ships goods to customers. However, sellers are forced to use Amazon’s fulfillment services even if they would rather use a competitor like UPS to gain preferential placement within Marketplace. Thus, while FBA charges are nominally for the logistical services that Amazon provides, because Amazon ties Marketplace and FBA together, they are really an additional fee for Marketplace.

Amazon sellers have no way to escape from these exorbitant tolls given Amazon’s market power. In 2021, Amazon expanded to 56.7% of the US e-commerce market. As such, there is no viable alternative to Amazon for sellers. One seller, in the ILSR’s report, explained:

Amazon has us by the throat. We have tried numerous times to become independent of them. We tried [selling] though Poshmark, through Etsy, through Instagram, through Facebook. We tried Wish. We tried Sears. Even selling on multiple sites, I was doing only a tenth of the volume that we had on Amazon. They own such a huge chunk of the market.

Amazon cornered the market by strategically lowering their prices to match prices offered by competitors. While, theoretically, competitors could offer lower fees, allowing sellers to lower prices, Amazon uses artificial intelligence based software to patrol the web and look for its sellers offering lower prices than they do on Amazon. If it finds lower prices, Amazon forces its sellers to lower their price on Amazon to match, without offering a reduction in exorbitant fees. This practice thwarts any potential competition to Amazon’s dominance in e-commerce.

One critique of this narrative is that Amazon has gotten into the retail game on its own by offering its own products. If Amazon is able to use its market power to extract all the profit of independent retailers through feed, then why does Amazon feel the need to get into the retail game? The reason is that Amazon’s retail division is designed to compete with Walmart and other chain stores that offer online shopping. By taking control over the essential products (lightbulbs, toilet paper, cheap clothing, ect.) that consumers go to these stores for, Amazon has more control over the prices these products are offered for on Marketplace. Thus, Amazon can undercut potential online shopping competitors in price and lock them out of the market.

There needs to be a cocktail of responses from policy makers in order to protect small businesses on Amazon. First, policy makers need to split Amazon up into its component parts. Combining retailing, web services, advertising, supply chain logistics and an online marketplace all in one company gives Amazon inordinate power over its small businesses. One clear example of this, which I previously discussed, is how Amazon uses its online Marketplace power to force small businesses to use its logistics branch (Amazon Fulfillment Services). Similarly, Amazon is able to use its retailing division to block potential competitors for online retailing.

However, separation of these different business lines will likely not be sufficient to protect sellers. Instead, we need new legislation that mandates that Amazon acts as a common carrier: that it can not use its power to discriminate between different online sellers through prices or placement in search results.

Finally, it is worth considering potential price regulation of the fees that Amazon can charge to its sellers. By putting a cap on the exorbitant fees Amazon can charge, small businesses will remain viable on the platform.

Whatever the cocktail of policies put together, it is clear that something needs to change. Amazon’s high fees creates an alarmingly low profit margin for sellers, meaning that only large businesses can survive on the platform. The result is increased consolidation in an already incredibly consolidated economy; policy change is necessary not just to prevent Amazon from exploiting small businesses but to ensure an equitable distribution of economic power across the economy as a whole.

Neil is a Junior in the College majoring in Government and Economics with a minor in Philosophy. Originally from Arlington, MA, he enjoys running, grilling and considers himself a coffee connoisseur.