The true nature of the Facebook papers: surveillance capitalism

NEIL TRACEY: This week marks roughly a month since former Facebook executive and data scientist Frances Haugen disclosed thousands of pages of insider documents about Facebook’s inner workings to the SEC and later to Congress. These documents dubbed the “Facebook Papers,” detail Facebook’s inner conflict over combating misinformation on its platform. The Facebook Papers have sparked a new wave of backlash against Facebook. Most of the coverage and editorializing has focused on Facebook’s incredible, antidemocratic power, and how they have misused it. The Facebook papers reveal that Facebook is well aware of the extent to which their platform promotes misinformation, and can do so, but chooses not to. While this analysis is valuable, Facebook’s true power is more profound than this. As such, Facebook threatens our democracy and personal sovereignty.

Shoshana Zuboff, a Harvard philosopher and social psychologist who has extensively studied digital capitalism, believes that we need a new terminology and philosophical construction to truly understand the role that data currently plays in the economy. Zuboff explains that what we are seeing is truly unprecedented; as such, it can not be understood under the old paradigm of economics. Yes, Facebook is a monopoly. Yes, Facebook lacks data privacy. es, Facebook promotes misinformation. However, these concepts are insufficient to explain this new economy. In her book The Age of Surveillance Capitalism, Zuboff explains that there is a new “logic of accumulation” of data. This new order “ha[s] broken away from the norms and practices that [previously defined] the history of capitalism and in the process, something startling and unprecedented has emerged.” A new idea is needed to understand this new order: surveillance capitalism.

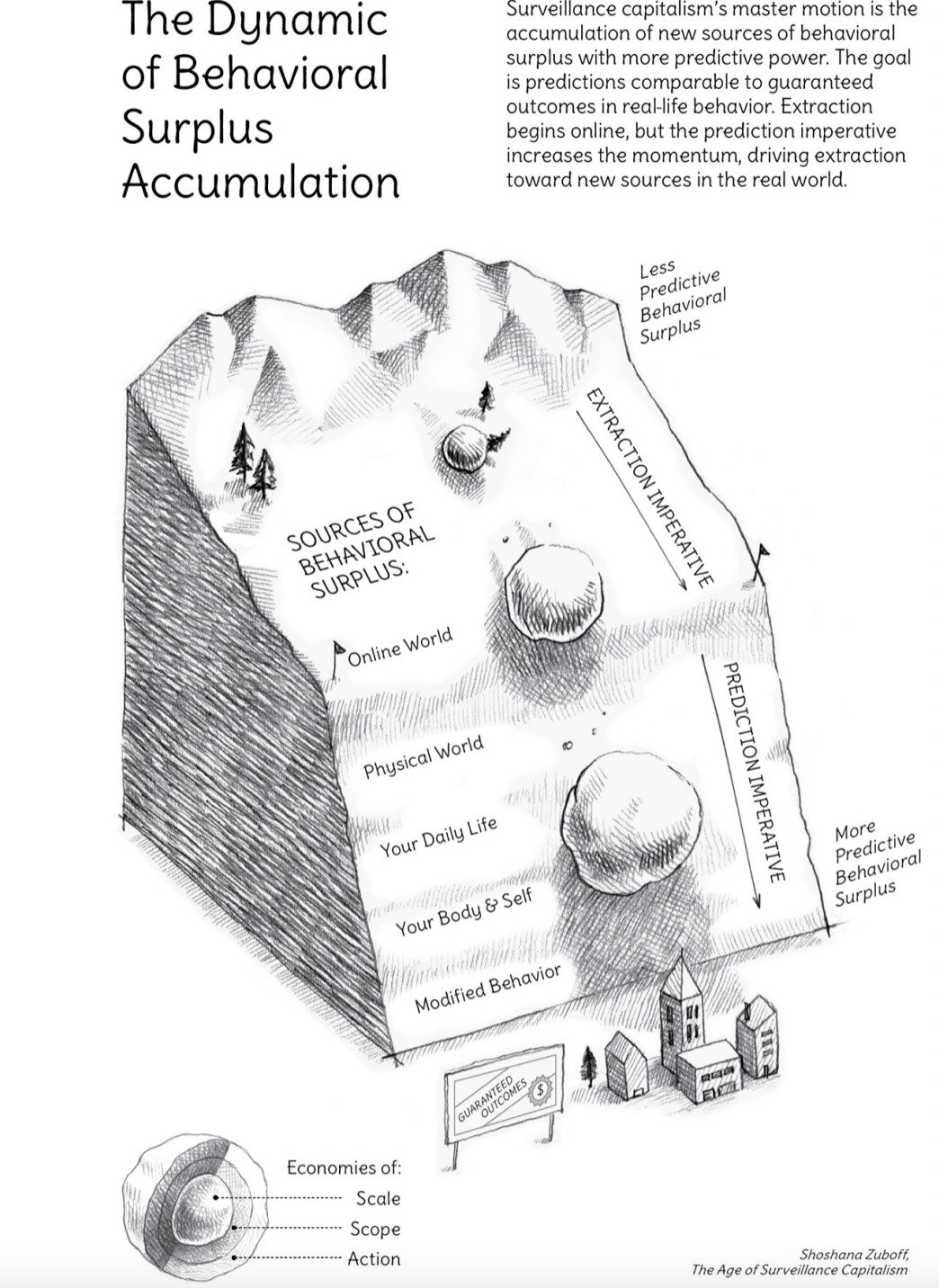

Zuboff defines surveillance capitalism as both “a new economic order that claims human experience as raw material that claims human experience as free raw material for hidden commercial practices of extraction, prediction and sales'' and “an expropriation of critical human rights that is best understood as a coup from above: an overthrow of the people’s sovereignty.” Human experience, collected as data through social media, is the building block of this economic system. This data is partially used to improve the service itself, and thereby collect more data. The rest is translated into a “behavioral surplus” - leftover data that is owned by the company and formed by machine learning technology into the ultimate product: prediction and manipulation of consumer’s future behavior. This product is thus ultimately data-driven.

Surveillance capitalists are on a constant hunt for new data, integrating their platforms, making their service more attractive, and finding new ways to extract data from users to better their predictions. One notable example of this is Google Street View. In 2010, the German Federal Commission for Data Protection revealed that Google Street View cars were secretly collecting personal information from private wifi networks that it passed. Data allows them to model just how to shape consumer behavior. They can tell that you will be more susceptible to buy a mother’s day card when you are feeling lonely, for example, and then can gently nudge you towards this feeling by curating the information you see. This constructed future behavior is then sold to companies to sell products. In this way, consumers’ sovereignty is violated - consumers no longer have the capacity to make rational decisions as these decisions are pushed by the company. Thus, Zuboff explains that “surveillance capitalism operates as a challenge to the elemental right to the future tense, which accounts for the individual’s ability to imagine, intend, promise and construct a future.” This relationship between data and construction of user’s behavior is illustrated in the diagram below:

The “extraction imperative” constitutes the deluge of information necessary to create the prediction imperative, predictions about the user’s world, life, and self. The prediction imperative culminates in being able to use these predictions to create a modified behavior.

Outside of Facebook, one notable example of the sheer power of surveillance capitalism is the popular game Pokemon Go. Pokemon Go was an augmented reality game where players traveled the physical world to capture virtual “Pokemons.”Niantic Games explicitly created the game as a “social experiment” to see if they could shape consumers’ actions in the real world. Corporations, including bars, restaurants, and coffee shops could pay to have “pokemon stops” at their locations. Thus, consumers’ actions were altered in the real world for the benefit of surveillance capitalists. This same logic of predicting and shaping consumers’ behaviors is the ultimate product of every surveillance capitalist.

To make matters worse, consumers cannot opt out of surveillance capitalism. Surveillance capitalists design their products to make the costs of opting out high. Zuboff gives the example of a home system that controls your lighting, appliances, security system, and heating in one internet integrated system. If you do not give the system permission to collect your data, the company warns that the thermometer system will not be able to function properly. If you do not “willingly” give your data, your pipes will freeze. More profoundly, surveillance capital systems, including social media, are such a bedrock of modern society that they are necessary for social inclusion in society. Opting out of social capitalism means opting out of modern society. As such, the myth of consent is surveillance capitalism is just that: a myth.

To change surveillance capitalism, it is necessary to understand just how surveillance capitalists have avoided regulation in the past. Zuboff sees a cycle of behavior that surveillance capitalists use to preserve their systems. The four stages of this cycle are incursion, habituation, adaption, and redirection. The incursion stage is the original theft where surveillance capitalists unrelentingly law claim to every piece of data that they can lay their hands on. In the habituation stage, the surveillance capitalist outlasts the tedious bureaucratic processes that characterize public pushback.

While lawsuits languish in year-long court battles, the contested practices become even more established, habituating the public to them. Zuboff noted how technology companies repeatedly ignore subpoenas from enforcement agencies, simply paying the fines and moving on. In the adaptation stage, surveillance capitalists adopt superficial changes that are meant to appease immediate public opinion without fundamentally altering the nature of surveillance capitalism. This often includes promises to “self-regulate.” The final stage, redirection, is the only example of permanent change resulting from the cycle. In this stage, surveillance capitalists redirect data supply chains to give the appearance that they are no longer engaging in the contested activity. While this stage may constitute the closest thing to real change in the cycle, it does not undermine the fundamental logic of the accumulation of data that underpins surveillance capitalism.

While this all may seem very grim for anyone who is not a surveillance capitalist, several key takeaways can help create change. We need a new paradigm to understand the intersection of data and capitalism. Concepts such as monopoly and privacy are insufficient to explain the modern digital economy. To create change, we must build off of Zuboff’s understanding of surveillance capitalism to accurately describe the problems with the digital economy. Moreover, our old regulatory methods can not keep pace with surveillance capitalists. Perhaps, the way forward involves a combination of intense public pressure, regulatory battles, and new legislation. Perhaps, there must be a coordinated international effort to fight surveillance capitalists. Perhaps, nothing will change until there is a deep-seated public understanding of what surveillance capitalism is. I, certainly, do not know the answer. But only by public discourse to call our modern economy what it is— surveillance capitalism— can we hope to figure it out.

Neil is a Junior in the College majoring in Government with minors in Philosophy and Economics. Originally from Arlington, MA, he enjoys running, grilling and considers himself a coffee connoisseur.