Antitrust and labor

NEIL TRACEY: The recent labor shortage has given employees new power to demand better working conditions and new wages. This year alone, there have been over 178 strikes against employers and over 12 that included 1,000 or more employees. The increased pressure on employers has led to a moderate increase in wages. In order to sustain this pro-worker movement in the economy, it is important to understand why wages were stagnant until now, and how they might become stagnant once more. To do this, I plan to answer a very simple, but timely, question: what does antitrust enforcement mean for labor markets?

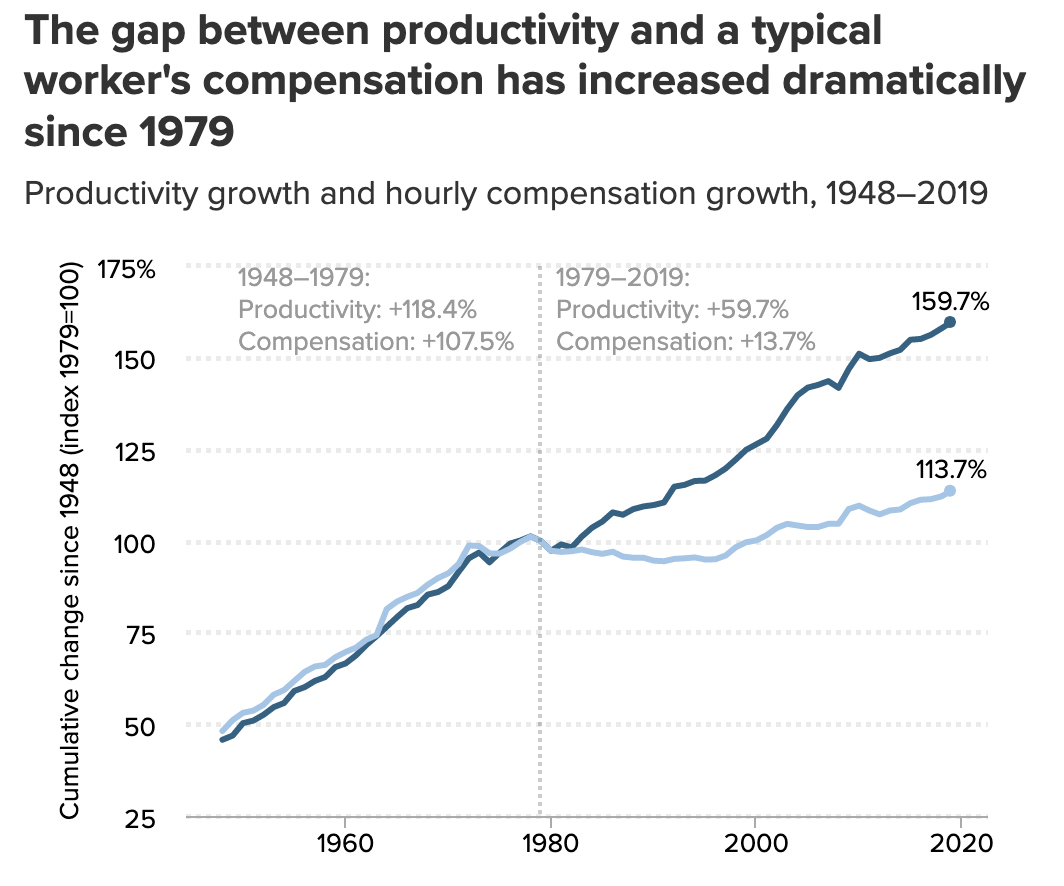

Since the early ’80s, we have seen the divergence between the average productive output of labor and the growth in wages. Historically, and under traditional economic theory, the two are correlated. As the chart below demonstrates, between 1948 and 1979, there was only a roughly 10% divergence between the growth of compensation and the growth of productivity - increased productivity should increase wages. In recent years, however, the two have become uncoupled. We have seen a high increase in productivity combined with a low increase in wages. Moreover, this decoupling has happened amid a tight labor market. In theory, low unemployment means that employers have to raise wages to compete for employees. However, until the recent most drastic shock, wages have failed to respond to historically low levels of unemployment.

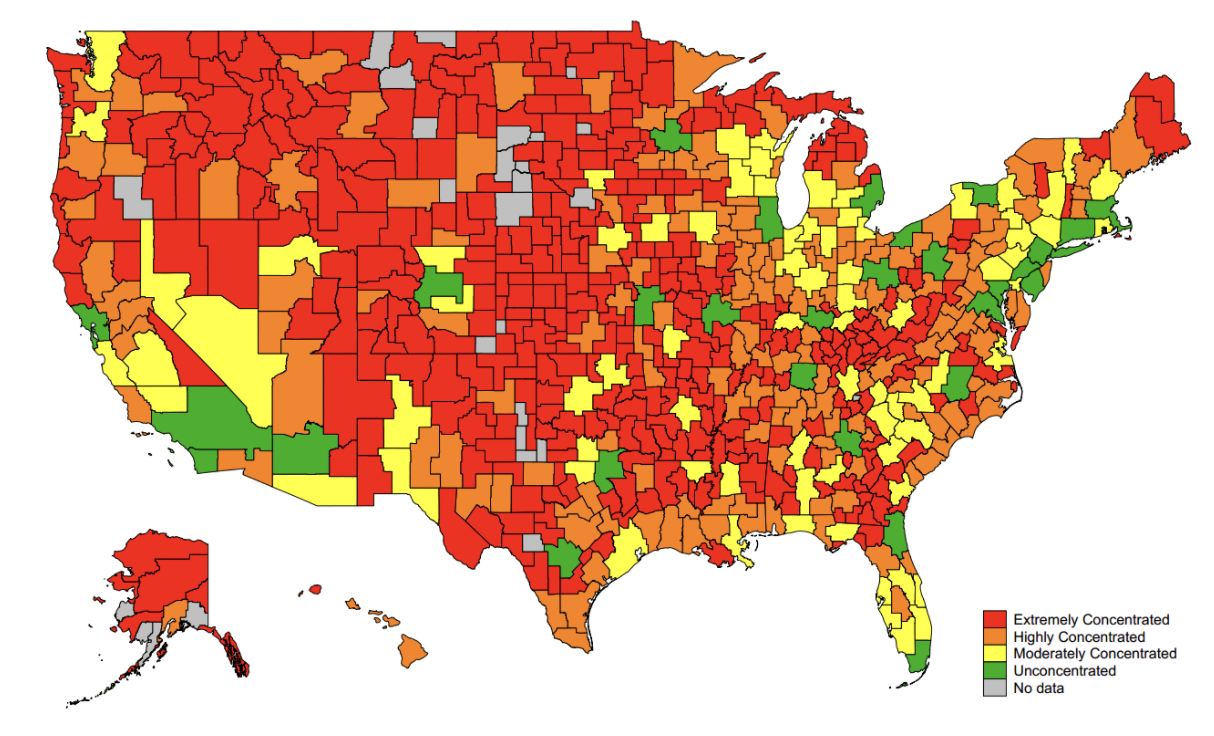

Recent research suggests that monopsony in the labor market may be the reason for this wage stagnation. One study, by José Azar, Ioana Marinescu, and Marshall Steinbaum, looked at 8,000 different geographical labor markets in the United States (based on possible commuting areas) and found that, based on the FTC-DOJ guidelines for what constitutes a concentrated market, the average labor market in the United States is highly concentrated. In the figure below, Azar and his co-authors map labor market concentration across the United States. While high levels of concentration can be found everywhere, monopsony power is especially concentrated in rural areas of the country, exacerbating regional inequality. As the researchers went along the distribution of concentration, from the 25% to 75% percentile, they found that wages decreased by as much as 17%. Moreover, researchers Benmelech, Nittai K. Bergman, and Hyunseob Kim confirmed this negative correlation between labor market concentration and wages. In addition, they looked at the effects of mergers on local labor markets, comparing before and after the merger in order to prove causality. They found that mergers in local labor markets without unions decreased wages.

In his recent book How Antitrust has Failed Workers, Eric Posner of the University of Chicago Law School explores how our current Antitrust regime has allowed for concentrated labor markets. Posner points out that Antitrust law applies to both supply and demand sides of the market and applies to both product markets and labor markets equally. Moreover, there is no theoretical reason why labor markets should be any less subject to anticompetitive behavior than any other market. Despite this, Posner notes that, historically, “antitrust law has rarely been used against labor-market bullies like employer cartels and labor monopsonists.” Without the threat of litigation, Posner believes that it is only logical that “profit-maximizing firms will look for opportunities to cartelize labor markets.”

To make matters worse, many big companies use no-poaching agreements to ensure that their employees do not go work for competitors in the same industry. These agreements are designed for high skilled professions where a company may have genuine concerns about ex-employees giving trade secrets to their competitor. No-poaching agreements, however, are employed by a remarkable number of blockbuster franchises. In a 2016 study, researchers Alan B. Krueger and Orley Ashenfelter found 58 major retail franchises that use these anti-competitive agreements including McDonald’s, Burger King, Jiffy Lube, and H&R Block. There is no plausible argument that no-poaching agreements are necessary to protect trade secrets in these service sector jobs. Instead, these agreements simply serve to drive down wages of service-sector employees. Moreover, these no-poaching agreements do not just apply to competition between different companies, but between different franchises of the same firm.

Thankfully, there has been some movement towards the incorporation of labor market considerations into the antitrust regime. In 2018, the Justice Department alleged Silicon Valley companies, including Google and Apple, participated in collusion for agreeing not to poach each other’s employees. The case ended in an over 400 million dollar settlement. Under the Biden Administration, we can hope to see more movement towards pro-worker Antitrust policy. Biden’s recent executive orders concerning antitrust included a new focus on labor markets and, following this lead, the DOJ Antitrust division has promised to focus additional resources on the labor market. Earlier this year, then acting Antitrust head Richard Powers explained that “The division has become increasingly alert to and concerned by business conduct and transactions that harm competition for working people.”

It is important to recognize that the federal and state antitrust enforcement agencies are only a small part of the antitrust enforcement regime - labor unions and private antitrust suits also play a critical role in antitrust enforcement. A decisive move by government officials to include labor monopsony in antitrust enforcement could signal the potential for antitrust litigation to raise wages and encourage pro-market behavior. The recent labor shortage has led to some increases in wages, but the question of whether or not this growth in wages will be sustained will come down to whether or not the labor markets can become competitive. The Biden Administration must act swiftly and decisively to permanently create a competitive labor market.

Neil is a Junior in the College majoring in Government with minors in Philosophy and Economics. Originally from Arlington, MA, he enjoys running, grilling and considers himself a coffee connoisseur.